On Learning: Memorization vs. Marination

And what Traditional West African Percussion taught me about internalizing new subject matter.

I’ve heard this so often that it’s become a sort of trope: School mostly rewards memorization —> regurgitation.

Sure, maybe.

The way we are evaluated in school is largely based on how we are able to perform on tests. And in order to perform well on a test, you need to put down just the right answer.

How one arrives at the right answer, “showing your work” notwithstanding, is another matter entirely. Did you memorize and regurgitate? Maybe. Or did you form a deep understanding of the subject matter such that you can reason your way through to find the right answer?

Importantly, is the answer even memorize-able? Or is the answer only “find-able” by someone with a deep understanding of the subject matter?

I was a decent student. That said, I must admit: Many times, as a student in the school system, I felt that we were moving far too quickly. I longed to be afforded more time to work on whatever topic caught my interest. I wanted to go deep. I wanted to marinate on it before moving on.

As I got older and took on the challenge of learning new skills, languages, etc. as an adult, this concept of marinating has come up time and time again. Lets’ explore the process and merits of learning through marination — spending significant time on a narrow scope to internalize the concepts in a unique way, as opposed to memorization — committing to memory “the right answers,” or something close to them.

I’ll lead with an example told via my personal story and connection to learning Traditional West African Percussion.

First off: Check it out!

And…

Above shows two (of many, many) examples of Traditional West African Percussion. I use this term (Traditional West African Percussion) to refer to the drum, the dance, the chanting, and any other aspects of what is seen in the videos above that would be viewed as distinct and unique to the layman “Westerner” (American).

The traditional way to learn this drumming is to sit and play: Sometimes by yourself; sometimes in a group; but often, alongside a Djembefola — a (typically quite senior) master drummer.

I went to Guinea, West Africa in 2018. I played with numerous other students, many of whom were from Europe and Asia. We were there to immerse ourselves in the culture, to feel its roots, and to practice alongside a Djembefola or three. To put it bluntly, I was in way over my head! I had just discovered this genre of music about 5 years earlier. And I was, at best, a “street” musician. I use this term similarly to how a varsity, college, or professional basketball player would think of a “street” basketball player baller. It’s not a pejorative (more on this later). In some ways, it’s a compliment. But most of all, it means that I lacked in formal training. I had many hours under my belt playing in the park and for dance troupes with other experienced players. But I had fewer than ten hours of formal study. And on this trip were mostly advanced players with hundreds of hours or more of formal study.

There came a time on our trip, among the literal ten hours of practice in each day, for a brief period of improvisation. And when it came time to improvise (where we would play a solo over the accompaniments played by all the fellow drummers in the group), I miraculously became not just a standout, but the top drummer of all the students! It became immediately evident. The other drummers commented on it with admiration and surprise.

It was a much needed confidence boost after getting my ass handed to me, frankly, by the other players. While I was easily in the bottom 25% in experience and ability when it came to the formally-charted music, I stood out when improvising. And if ability to improvise can be proxied by comfort level and feeling (or, the extent by which the drummer has internalized the nuances of the music), it seems that I was far ahead of my more formally-trained peers.

This came up again more recently as I joined a new study group. The teacher, in my first class, seemed perplexed by the mismatch in my feel vs. my technical ability compared to the other drummers in the class. The technical component wasn’t beginner level, more intermediate. But my feel was advanced, he thought.

It seemed that my time drumming in the park, playing the simple parts over and over again in mind numbing repetition, allowed the freedom for my mind to wander, to explore in a sort of way that may not be possible when you are not bored. When you are being stretched by the technical and academic work of learning, perhaps memorizing new parts, it seems there may be a lack of opportunity to marinate on and internalize the music. But internalization, and making it your own, is exactly what ultimately separates the copycat from the Djembefola.

This scales, too, to another favorite pastime of mine: Basketball.

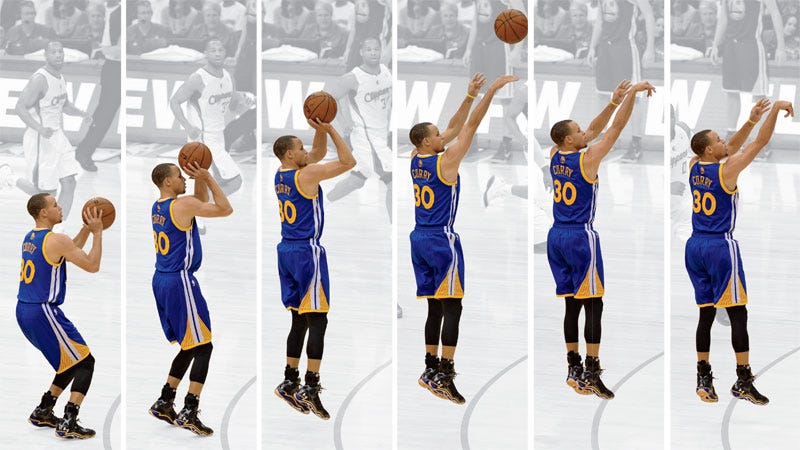

It wasn’t until I (first via intuition, and later confirmed by the greatest shooter of all-time, Steph Curry, sharing his routine) learned that the best way to develop my 26-foot shot was to develop my 2-foot shot that, once again, mind-numbing repetition is the answer. I was not the best 3-point shooter. And I wanted to change that. To keep the story short, I developed a routine where, for 2 months straight, I would not allow myself to take any other shots until I have made 100 2-foot shots, hyperfocusing on form and mindset. And once I made those hundred, I wouldn’t go far. Next up was 5-foot shots. I’d have to make 50 of them. Then 15-foot shots. After two months, I was delighted at how quickly my three-pointer improved. I’d improve from a self-rated 3/10 to a 5/10. And there is still plenty of runway for me to continue improving.

So how does this fit in to the overarching message in this passage?

Not only did the 2-foot shots limit the downtime between shots (retrieving your rebound when you’re standing nearly under the hoop doesn’t take much time, it turns out). But it also allowed to simplify, focus on nuance, rather than the power generation required for a 20-footer (or further). I was able to marinate and fine-tune. Rather than jump right into the hard stuff, I let myself get bored to death with the easy stuff. And this is exactly what made me far more successful with the sexier, harder stuff: The three-pointer.

As a side, I’ve noticed that all of the top NBA players, if not simply all of the NBA players, period (they are, roughly, the top 450 basketball players in the world, after all), preach (at length) and practice the benefits of routine. I equate this to what I call marination — they practice with mind-numbing repetition to internalize and truly become world-class at their craft. They don’t just watch and replicate. They put in so many reps attempting to do the same exact thing that even a 0.0001% deviation from the norm stands out. They say that to truly learn something, you should teach it. I think that’s right. And I also think it’s right to say that in order to truly learn something, you need to think about it til your eyes bleed. Like applying a sort of scientific method, these players are able to adopt subtle variations that work, and discard those which don’t, thanks to hundreds of thousands of repetitions. And that is how they become world class — searing what does work into their mind, body, and subconscious, while also stumbling upon the tiny tweaks that will improve their abilities even more.

It’s one thing to watch videos of Stephen Curry and reproduce something that looks nearly identical to his shot (undoubtedly with less success than his). It’s another entirely to watch video of Stephen Curry, use that as a starting point, and then put in hundreds of thousands of reps to make it your own. You will stumble upon numerous tweaks that may work better for your proportions, motor neurons, etc. You will make it your own. The final result may look nothing like what Steph has, even if you enjoy similar shooting success to his.

And this is exactly the marination. I pass no judgement on copycats. There is a lot of benefit in copying something that works well. Some may call this the Kobe Bryant approach (via copycat’ing Michael Jordan): But note that Kobe still put in an epic number of hours that was nearly mythical to his peers. Kobe’s end result was similar to MJ’s. But no doubt, had he discovered some key areas of discrepancy in what works for him vs. What worked for MJ, he’d have adjusted.

And so it seems, to become truly world class at something, which ought be the goal for all of us(!), it will become essential to marinate on it and make it your own. The final output may resemble a copycat. It may result in something else entirely. But the process of mind-numbing repetition (you know you’re doing it right if you are extremely bored!) cannot be skipped.

This marination concept isn't limited to drumming or basketball. It extends into almost every aspect of our lives, especially in how we learn and internalize new knowledge and skills. Consider language learning: You could memorize vocabulary and grammar rules (and to some extent, you need to). But it's only through the repetitive practice of speaking, listening, and even thinking in the new language that you truly begin to "speak" it. The same goes for computer programming, data analysis, and so on. This process, much like marinating a piece of meat, allows the flavors of the language to seep into your cognitive framework, enabling a more natural and fluent use.

Why is marination so effective? I’d be interested in your thoughts, in the comments, personal anecdotes included. But perhaps the answer lies in the depth of understanding it fosters. When you marinate in a subject, you're not just learning the what. But also the why and the how. This deep dive builds a foundational understanding that allows for greater creativity, adaptability, and innovation. You're not just following a set of rules; you're understanding the principles behind them and thus can apply them in new, unique ways.

Moreover, marination promotes a form of learning that is emotionally and cognitively engaging. It's not passive absorption but active exploration. Despite it being boring at a superficial level, it’s fun at a deeper level! This engagement is crucial for long-term retention and application of knowledge.

So, how do you apply this to your life? Start by choosing a subject or skill you're passionate about. Then, dedicate time to not just learn it but live it. Immerse yourself in it. Play with it. Experiment and explore different facets of it. Be patient, as marination takes time. And most importantly, embrace the boredom that comes with repetition. It's a sign that you're ingraining the skill deeply into your psyche.

In conclusion, whether it's West African drumming, basketball, language learning, and/or learning to program computers, the principle remains the same: True mastery comes not from mere memorization, but from the deep, repetitive, and reflective practice of marination. So, take your time, dive deep, and enjoy the journey of becoming truly world-class in your chosen field. Remember, it's not just about learning; it's about internalizing and making it an inseparable part of who you are.

To tie this into the timing of this post (the new year), I will share a goal have a goal in 2024: be bored. Don’t fill the boredom. Continue to return to the same basic tasks and concepts over and over and over again. Embrace and seek out boredom. I have experienced a lifetime’s worth of novelty before the age of 35 already!

Thank you for reading! I’d love to hear your responses and reflections in the comments and to engage in discussion. What are you studying in the new year?

And on the theme of music, I leave you with Prince. Apparently, he’d agree with me here!!